As Y.A. Tittle’s memory fades and his body breaks down, the Hall of Fame QB finds fleeting moments of solace in a daughter’s love and a final trip home.

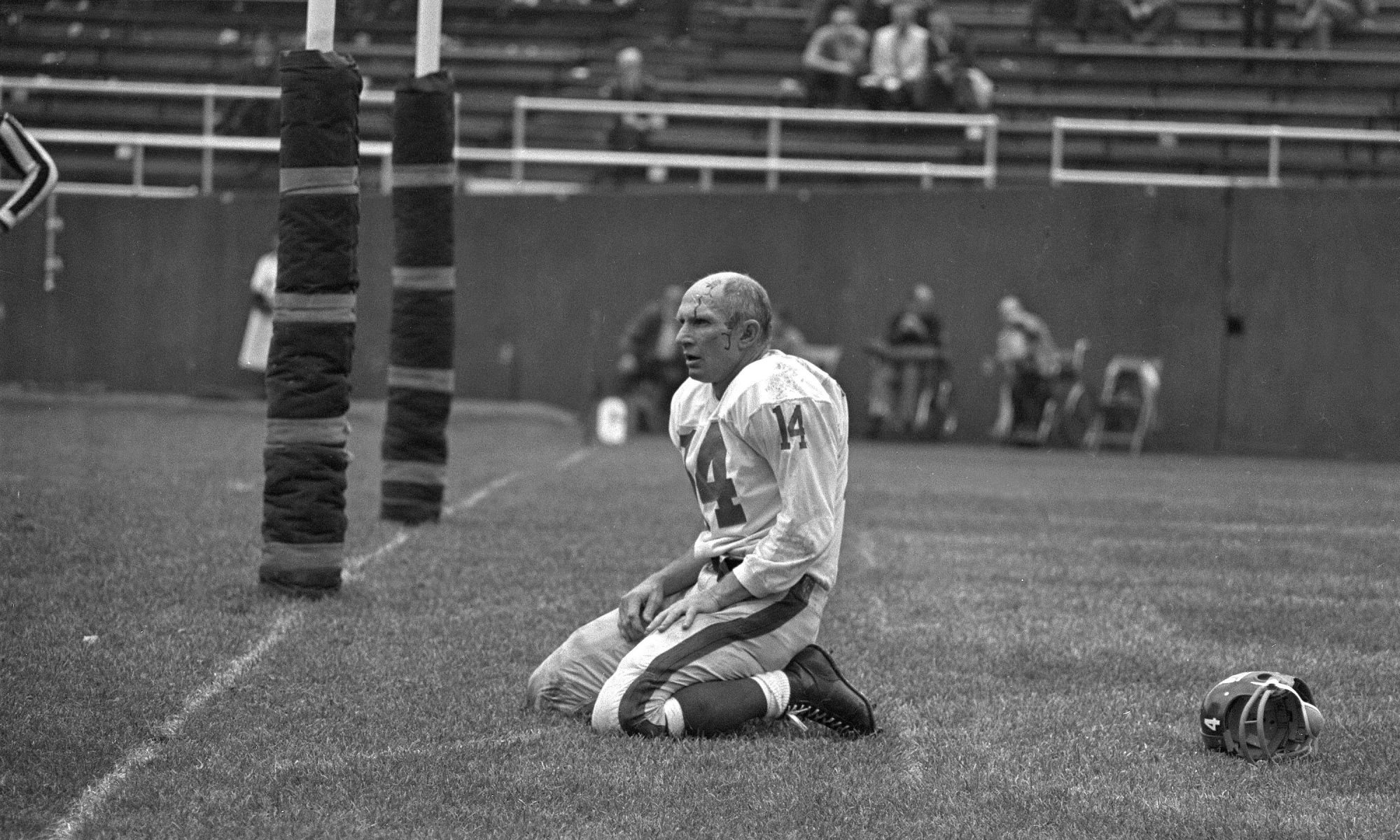

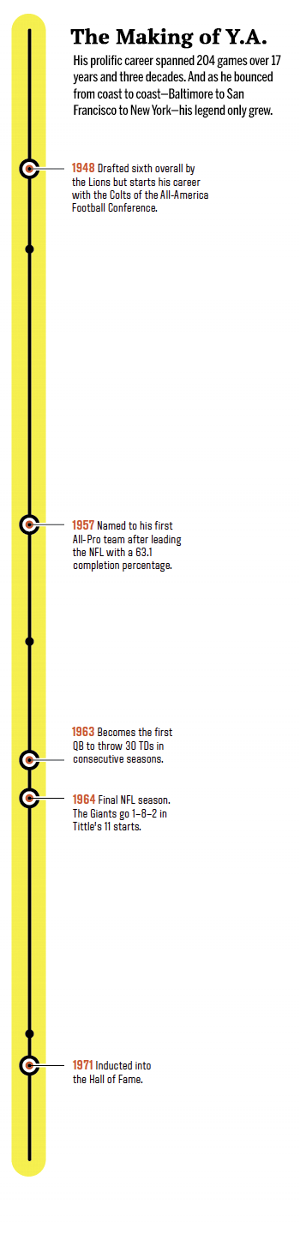

YOU REMEMBER THE picture. Y.A. Tittle is on his knees in the end zone after throwing an interception that was returned for a touchdown. Swollen hands on his thigh pads, eyes fixed on the grass, he is helmetless and bleeding from the head, one dark stream snaking down his face, another curling near his ear. His shoulder pads make him seem hunched over, resigned, broken down. The black-and-white photo was taken in 1964, the final year of Tittle’s career. It hangs in a silver frame at his home in Atherton, California, not with the prominence befitting one of the most iconic pictures in sports history but lost among many mementos from a Hall of Fame career. The picture is now 50 years old, and Tittle is now 87. He does not remember much anymore, but that photo is seared in his mind. “The blood picture,” he calls it. He hates it.

HE REMEMBERS A place. It is in Texas.

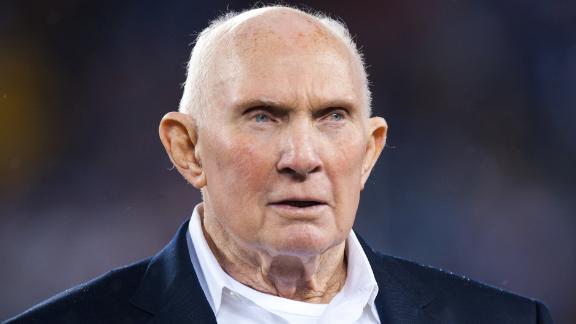

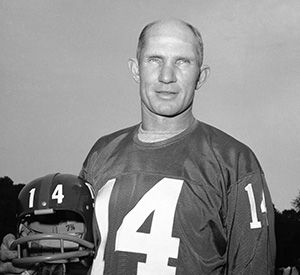

On a December morning, he’s sitting in his usual spot on his couch, flipping through a photo album. His breathing is labored. There is fluid in his lungs. Waistline aside, Tittle doesn’t look much different now than he did in his playing days: bald head, high cheekbones, blue eyes that glow from deep sockets, ears that have yet to be grown into. His skin is raw and flaky, and when he scratches a patch on his head, a familiar line of blood sometimes trickles down. He shares his large house with his full-time helper, a saint of a woman named Anna. His daughter, Dianne de Laet, sits nearest him, leaning in as he touches each yellowed picture.

“That’s at Marshall High School!” Y.A. says, pointing to a shot of himself in a football uniform worn long ago, long sleeves and a leather helmet. That takes Y.A. back to his tiny hometown of Marshall, Texas, near the Louisiana border. Friday nights in the town square, where “I’d neck with a girl, if I was lucky.” Brown pig sandwiches at Neely’s barbecue. And football, always football. In 1943, he says, Marshall High traveled 200 miles to play Waco, ranked second in the state. The Mavericks pulled off the upset, and on the couch he recites the beginning of the newspaper story: “From the piney woods of East Texas came the challenging roar of the Marshall Mavericks, led by a tall, lanky redhead with a magical name: Yelberton Abraham Tittle.”

He is slightly embarrassed as he utters his full name. As a teenager he reduced it to initials, and it later became legend. Remembering his Texas days seems to bring a youthful spirit out of him, which is why Dianne gave him this album today. But then he flips to a photo of himself during his college days at Louisiana State, and something slips. “Where did you get these pictures?” he says to Dianne. “I haven’t seen them.”

ESPN The Magazine: Hall of Fame QB Y.A. Tittle at age 87In discussing Hall of Fame quarterback Y.A. Tittle at age 87, Tittle’s daughter Dianne De Laet rekindles memories of the iconic 50-year-old photo of her father.

She knows that he has seen these pictures many times, of course. Some even hang in his house. Dianne is 64 years old, with blue eyes shining from a face that she tries to keep out of the sun, and it is hard for her to watch each old photo bring the joy of a new discovery. She lives feeling a loss for her father, a loss that he doesn’t feel for himself — until something stirs it up. That happens when Y.A. mentions that his phone has been strangely quiet, considering that Christmas is in a few days. He suddenly realizes that he hasn’t heard from his best friend from high school. “I don’t think Albert died, did he?” he says.

“He died,” Dianne says, with the forced patience of having to repeat news over and over. “He died a couple months ago.”

“Oh yeah, right. He was such a good friend.”

“Jim Cason” — Y.A.’s best friend from the NFL — “also died about a month ago,” Dianne says.

“You said Jim Cason died too?”

“He’s gone.”

“Damn,” Y.A. says, closing the album.

“You’re the last leaf on the tree,” Dianne says.

SHE REMEMBERS HER dad. It’s not the person he is now. Some years back, doctors diagnosed dementia. Friends always ask Dianne if his condition is related to football. She can’t know for sure but thinks he’s simply getting older. In the past year, Y.A.’s memory loop has tightened like a noose. He repeats himself every minute or so. It has left a football legend, whose speaking engagements used to take him around the country, incapable of holding normal conversation and limited to a handful of topics: his late wife, Minnette; his four children, seven grandchildren and five great-grandchildren; football; the hope of a vodka rocks each day at 5 p.m.; and, most of all, his hometown of Marshall, Texas.

Anyone familiar with Tittle’s football career knows that it wasn’t supposed to be this way. His body was supposed to crumble, not his mind. He was famous during his 17-year career — as a backup with the Colts, as a star with the 49ers and as a legend with the Giants — for not only playing through pain but for retaining a wit in the face of crushing losses. But Dianne has watched her dad regress in inches, too small to notice during daily visits from her nearby house but devastating when considered in their totality. “I haven’t lost him,” she says. “But I’m losing him.”

Still, she believes — hopes — that the dad she’s known all her life resides somewhere inside, bound up and waiting to be freed. That person arrives in flashes, mostly when he talks about a party that he has hosted for 27 years in a row at his house on the shores of Caddo Lake, 20 minutes northeast of Marshall. What began as a way to give Tittle’s former teammates a taste of East Texas evolved into an annual event, a rite of spring, with friends from every stage of his life sitting on the porch as the sun set, drinking beers and eating barbecue, strumming guitars and howling country songs, listening to the host’s yarns grow more elaborate as the cooler emptied and night descended into morning. His golden rule of storytelling: “Lie to tell a truth.” When folks would mercifully stumble to bed, Y.A. would issue an order: Be at the dock to go fishing at 7 a.m. They would always be there, black coffee in hand. Y.A. would usually oversleep.

That party is never far from his mind, even now. In December, as if on cue, the anticipation of hosting for a 28th year creeps into Y.A.’s consciousness. “We have to do it,” he says to Dianne.

She is wary. Most of his teammates are dead. The prospect of a few widows surrounding her confused and crestfallen dad seems terrifying. But in California, he spends his days in the TV room of an oversized house as his memory evaporates. Maybe, she wonders, his memory can briefly be restored in Marshall. Maybe geography can somehow transcend disease.

“We’re going,” Dianne says.

DIANNE HOPES SHE can give her dad the kind of miracle he once gave her. On Dec. 17, 1949, in Houston, Y.A. was playing in a charity football game when suddenly an eerie feeling told him to go home. He hitchhiked four hours to his house in Marshall, and early the next morning, Minnette, pregnant with their first child, awoke covered in blood. She had suffered a placental abruption and was hemorrhaging. Minnette was rushed to the hospital. Men weren’t allowed in the delivery rooms back then, so Y.A. pounded on the door, desperate for any update. Minnette survived. Their child, a little girl, had gone so long with so little oxygen that doctors pronounced her dead on her birth certificate. But the doctors were wrong. Dianne was alive — 4 trembling pounds, cradled in her dad’s hands.

So it’s fitting and somewhat ironic that of all the Tittle kids, Dianne is the one whom Y.A. now calls “my quarterback. I do what she says.” In a family of athletes, she suffered from exercise-induced anaphylaxis — potentially fatal allergic reactions brought on by physical activity. Still, she grew up trying hopelessly to connect with her dad. She watched all of his games, studying them for clues into what football revealed about him. Fans saw him as a star, larger than life. She saw him as human — a target on a field, a limping hero at home. Y.A. tried to bond with his daughter by ironing her clothes, but at heart he was the type of father who had no sympathy for splinters or stubbed toes and who wouldn’t talk football without one of his sons present.

It was not easy for a country boy from Texas to raise a beautiful teenage daughter in the 1960s. He initially disapproved of her marrying her hippie boyfriend, Steve de Laet, whom she met at the University of Colorado. And he initially disapproved of her decision to become a poet and harpist too. “The only Sappho I ever knew played for the Green Bay Packers,” he liked to say.

In 1981, Dianne ran a marathon, and when her allergy began to fight her from the inside, hardening her mouth and swelling her skin, she thought about how her dad always played through pain — through blood, even — and she finished. At a family gathering a year later, Dianne said: “Dad, sit down. I’m going to do something for you on the harp.”

She recited one of her original poems, and afterward Y.A. said, “What Greek was that?”

“Dad, it’s called ‘The Hero.’ It’s about you.”

Dianne has tentatively planned the annual party for March, but Y.A.’s health might prevent him from flying. In January, Y.A.’s breathing was so bad he thought he was dying. “This is it,” he told Dianne. He was placed on oxygen. But over months of daily conversations with his “little bitty brother” Don — he’s 84 — Y.A. asks hundreds of times when they’re going to Caddo Lake. Finally, Dianne books the party for the last Friday in April, but days before they are due to leave, Y.A. comes down with bronchitis. They board the plane to Dallas anyway. On the flight, he collapses from lack of oxygen; passengers have to help him off the floor. The entire trip seems like a bad idea. But then Don picks up Dianne, Y.A. and Anna at the airport, and they drive three hours east, off I-20 and to the end of a long country road, where a white house emerges from the blooming dogwoods. A sign reads: TITTLE’S BAYOU COUNTRY EST.

“It’s magical,” Y.A. says.

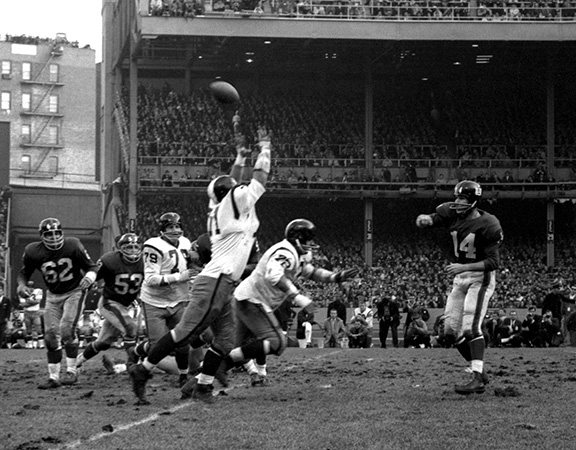

When the topic of his NFL-record seven-TD game comes up, Tittle says, “I didn’t know I was that good.” John Lindsay/AP Images

THEY SPEND THE afternoon on the back porch, staring at the lake. A breeze crosses through. Condensation from cold beer leaves rings on their table. Dianne studies her dad, hungry for flickers of memory, but he seems to be getting worse. Ten or so times each hour, he utters a version of this: “I grew up in Marshall, Texas. I went to Marshall High School — the Marshall Mavericks. I went to LSU to play football so that I could be closer to my older brother Jack, who played at Tulane. He was my hero.”

He hollers at Anna to bring him a vodka rocks and makes a few crude jokes, as if returning home has transplanted him to his teenage years. It’s all too much for Dianne. She walks to the dock and stares at the muddy water. It’s clear that there won’t be any magic on this trip. “His memory is gone,” she says, as if she needs to confirm it to herself. The party seems like a looming disaster. One of his few living high school teammates can’t make it. Her brothers are unable to attend. She’s out of energy and patience, and she feels guilty about both. Her eyes turn glassy. Something more than a party is at stake.

“You’re witnessing a family tragedy,” she says.

The lake seems to calm her, as it did the dozens of times she came here as a child. Soon she remembers today’s tiny moments that made her smile. During lunch at Neely’s barbecue — a Marshall staple almost as old as Y.A. is — everyone stopped and stared and pointed. Waitresses wanted a picture. Two teenagers approached him, calling him Mr. Tittle. Y.A. sat with them over brown pig sandwiches, talking about their football careers, not his. When it came time to leave, Y.A. reached for his wallet — he always pays — but the boys had already picked up the tab. It gave Y.A. a fleeting moment of honor, and it gave Dianne a fleeting moment of reassurance. She sometimes forgets that he is still a sports icon, even as she’s more protective of him than ever.

It’s dark now, and the mosquitoes are fierce. Dianne heads back to the house. Y.A. slowly lumbers inside from the porch. He sinks into a couch, panting so hard that it resembles a growl. It’s been a long day.

“You still breathing?” Don asks.

“I’m still breathing,” Y.A. says.

Y.A. COUGHS HARD most of the night, and by morning he is exhausted and croaking, his voice a scratchy wisp. But he has enough energy to venture into Marshall for a glimpse of his childhood, maybe the last. In the passenger seat of an SUV, he seems more alert, guiding Dianne through the outskirts of town as if he’d never left. They drive a mile down a thin, sleepy road and over a hill — a stretch he used to walk in the dark after football practice — until they arrive at a grassy lot, barren except for the crumbled foundation of a brick house that burned down a few years ago. A NO TRESPASSING sign hangs on a tree.

“Here it is,” Y.A. says. “I grew up here.”

They park on the lawn. A man from a nearby porch looks over suspiciously, then turns away. “This brings back so many memories,” Y.A. says. Dianne sits in the car, waiting to hear stories that she’s heard many times. He used to tell her about the hundreds of bushes that filled the yard and how in 1936, at age 10, Y.A. would pretend to be Sammy Baugh, taking a snap, rolling right, throwing to them. “They were my receivers,” he would say. The ball would lodge in a bush and he’d run to it, then throw to another, then another, for hours — Complete! Twenty-five yards! Touchdown! — fighting through asthma, through an allergy to grass, dodging snakes, sick with himself if he missed two bushes in a row, fascinated with spinning a ball long and well. His father, Abe, would come home from his job at the post office and be furious, his yard decimated. But Y.A. couldn’t stop. Nothing made him feel so alive.

It’s quiet in the car.

“This is a bit sad for me,” Y.A. says.

Seconds pass. “What are we going to do with this property, Dianne?” he says.

“Dad,” she says, trying hard not to tear up, “a young woman owns it.”

Again, silence. As Dianne slowly steers the car away, she says, “This might be our last trip out here.” Soon after, Y.A.’s sadness seems to have cleared from his mind like a bad throw. He directs Dianne past the cemetery where his parents rest, past the old grocery store, past the Harrison County Courthouse, to a brick building. “This is the old Marshall Mavericks High School,” Y.A. says.

Dianne slows down, but Y.A. doesn’t want to stop. He tells her to turn right, then left, until she pulls up alongside a park, fenced up and unkempt.

“This is the old football field,” he says.

Dianne hits the brakes. “Dad, I have to get out.” She jumps from the SUV, past men sitting on their cars and drinking out of brown paper bags, past rusted gates with broken locks, up concrete stairs blanketed in shattered glass, and looks out onto a shaggy field that she’s never seen before. “Wow,” she says.

She takes off her shoes. She needs to run. She owes her life to this field. It wasn’t where her parents first made eyes — that was in the town square — but it’s where they fell in love. Before he graduated from high school, Y.A. gave Minnette a bracelet with their initials in hearts. He left for LSU, she for the University of Arkansas, putting their relationship on hold. As a senior, Y.A. was asked by a reporter what he planned to do after graduating. “Marry my high school sweetheart and play professional football,” he said. Minnette’s boyfriend at the time was not amused. Months later, she and Y.A. were married.

A train whistles by. Dianne reaches the end zone and raps her knuckles against the rusted goalpost. She stands with her hands on her hips, tears and sweat soaking her face …

Y.A. slams the horn, ready to leave. Dianne takes a final look and climbs into the car, adrenaline filling her chest. Before she can turn the keys, her dad does something rare: He begins to sing. When those old Marshall Men all fall in line, we’re going to win that game, another time. And for the dear old school we love so well, we’re going to fight, fight, fight and give them all hell!

She is in awe. Since she landed, she’s been questioning why she made this trip. Is it for her dad? For her? Is it to cling to a fanciful dream? Finally, she’s in a moment that beats the hell out of the alternative.

Two blocks later, Y.A. says, “Did we go by the old Marshall Mavericks High School?”

THAT AFTERNOON, OUTSIDE the house, an electrical worker approaches Y.A. as he gets out of the car. “I know who you are,” he says. “Y.A. Tittle. New York Giants. You’re a baaaaad boy!”

“Well, thank you,” Y.A. says.

A few minutes later, on the couch, he opens a dusty commemorative book celebrating the Giants. He turns each page slowly, back to front, present to past. Legends pass on the way to the middle of last century, to the era of Gifford, Huff and Tittle, a team of Hall of Famers known for losing championships as their peers on the Yankees — with whom they shared a stadium, a city and many rounds of drinks — became renowned for winning them. Y.A. stops at a black-and-white shot of a man standing alone on the field, covered in mud.

“That’s me,” he says.

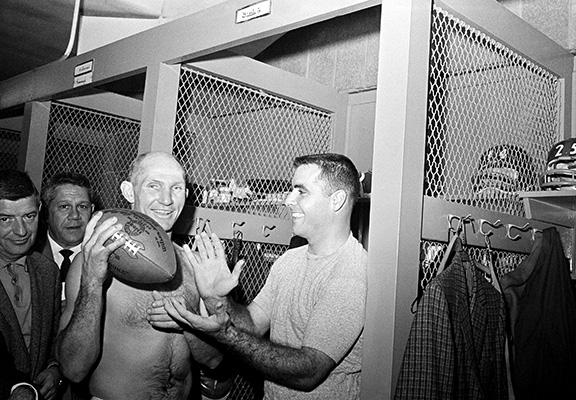

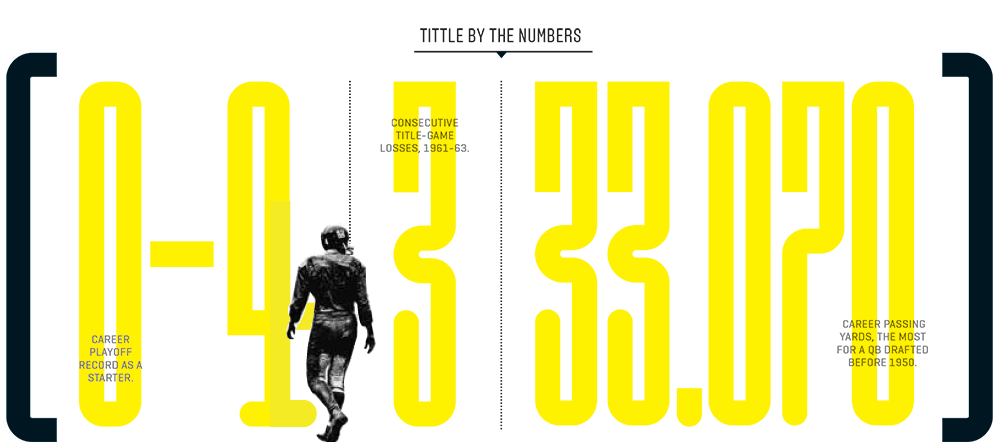

It’s from 1963. The same year in which Y.A., at age 37, set an NFL record with 36 touchdown passes. But he injured his knee early in the NFL title game against Chicago and threw five interceptions. It was his third straight loss in a championship game, and it effectively marked the end of his career. For years, he was the rare quarterback in the Hall of Fame without a title. It hurt. He always covered it up by poking fun at himself, making jokes about the weather during the championship games. But that last loss to the Bears was the worst day of his career: cold, bitter, violent. It marks him, even today. That game, he will never forget.

He turns to a page dedicated to the best performance of his career, against the Redskins in 1962, a game when he set a record with seven touchdown passes.

“I didn’t know I was that good,” he says.

Y.A. often talks about how he misses football. He misses the camaraderie, misses raising a vodka and saying, “We did it.” The game was, as Dianne likes to say, his “emotional home,” and in retirement in Atherton, he “was homesick for it.” Y.A. and Minnette fought a lot during those early empty years, struggling to adapt to a new reality; Dianne once screamed at them so loud to stop arguing that she lost her voice. Y.A. spent the next few decades running an insurance company, giving speeches and informally advising quarterbacks. He developed real estate in the Bay Area and made a lot of money and traveled the world and bought houses around the country. He buried his older brother, his sister, his wife and one of his sons. As the voids in his life piled up, the party at Caddo Lake became more important. Dianne considered it noble that her father strived to host it each year the way he had once strived for a championship. Each party was a win. That’s why she hates the blood picture too. The image of defeat that the world associates with her father does not resemble the man she grew up idolizing, the man she desperately hopes is still inside the current one, pining for what she calls one last “moment of victory.”

Y.A. closes the Giants book, and family members filter into the room. Tonight everyone wants to eat at the Longwood General Store, a roadside steakhouse. Back in the day, it was one of Y.A.’s favorite joints. Now he doesn’t want to go. “We came 3,500 miles to see this,” he says, pointing outside. “We got vodka and a meal and the lake. Why leave?”

Anna nudges him out the door. But then his memory circle restarts. Why leave? He refuses to get in the car. Family members buckle their seat belts, hoping the air of inevitability convinces him. But now he has to use the bathroom. Then his memory loop kicks in again, and he makes his old argument with the conviction of it being new. The family is exhausted. One of the most painful aspects of dementia is that it not only robs Y.A. of memory and identity, it robs him, as Dianne says, “of the capacity for joy.”

Five minutes later, Y.A. relents. The restaurant is a shack of Americana, with a stuffed alligator and old signs offering baths for 25 cents, exactly the type of place that could stir some memories. The family orders steaks and beers. Y.A. orders catfish and a glass of milk and barely utters a word all night.

IT’S FRIDAY. Party time. Dianne is stressed, hustling to prepare. Y.A. is stressed too, aware that something he cares about deeply is out of his control. “Dianne,” he says, “did you make a guest list?”

“No.”

“What kind of party doesn’t have a guest list?”

The truth is that she didn’t want to. She still doesn’t know who’s coming. But one of Y.A.’s oldest friends, a 90-year-old woman named Peggy, helped spread the word. And at 5 p.m., on a sunny and warm evening, guests arrive in droves — mostly neighbors and friends of the family. Y.A., dressed sharp in a navy blazer, greets everyone at the kitchen table. It’s hard to tell if he remembers any faces, if not names. The party swells to 50 or so people. Dianne leaves her dad’s side to catch up with old friends, reliving memories of her own.

A white-haired man approaches Y.A. and says, “I know every game you ever played, what you did and who you played with.”

“Oh yeah?” Y.A. says.

As Dianne struggled to connect with her dad, fans big and small were drawn to Tittle. Larry Stoddard/AP Images

He hands Y.A. a copy of the Marshall News Messenger from Sept. 30, 1943. Y.A. opens the fragile paper and scans the Mavericks roster until he sees Yelberton Abraham Tittle. He shakes his head.

“I’ve got the worst name in the world,” he says.

The party moves to the porch, and Y.A. sits in front of a guitar trio, tapping his feet. Every few minutes he repeats a thought as though it has just occurred to him. He requests “On the Road Again” over and over, and the band acquiesces most of the time. Between songs, his friends tell some of their favorite Y.A. stories. About how he used to fake injuries to keep from losing at tennis. How he was benched once because he refused to cede playcalling authority to the head coach. How he once persuaded a referee to eject his coach rather than throw a flag. Y.A. occasionally laughs but mostly stares at the lake.

Midnight nears. People leave one by one, kissing Y.A.’s head and saying, “God bless you.” He gives a thumbs-up for the cameras, and he autographs the only photo people brought — the blood picture, of course — by signing his name neatly on the white of his shoulder: Y.A. Tittle HOF ’71. A palpable finality lingers, as if everyone knows this might be the last time they see him.

The musicians move inside to the living room. Y.A. gives his all to hobble closer to them, one foot barely shuffling in front of the other. He sits on the couch, coughing. It is past his bedtime. Only six or so people remain. Y.A. holds his watered-down vodka but doesn’t drink, humming along to country songs.

Then someone plays the opening chords to “Amazing Grace.”

“Oh god,” Y.A. says.

His face reddens, like dye touching water. His eyes turn pink and wet. His breathing becomes deep and heavy. He brings his left fist to his eye, then puts down his drink, and soon both hands are pressed against his face. Memories are boiling up. Only he knows what, and soon they will be gone. The only thing that’s clear is that Y.A. Tittle is finally whole. He opens his mouth but can’t speak. He stares at the ground, his face glossy and damp, and begins to mouth the words, I once was lost but now am found.

SOMETHING FEELS DIFFERENT the next morning. Y.A. sits in a recliner with a blanket warming his legs, holding a coffee. Sun lights the room. Dianne and Anna lean on the counter; Don and Steve, Dianne’s husband, sit on the couch. All are tired, their voices scratchy. But they’re huddled in a sort of wonder. Y.A. is telling stories that have been told before but seem sweeter now.

“Tell the snake story, Dad,” Dianne says.

“We saw a big snake,” Y.A. begins. “This was 10, 15 years ago. Right out there. We were scared to death. I tell everyone to get back.

I get a hoe. I sneak up behind it and hit it and hit it and hit it and hit it. I was protecting my family. Finally, it flipped over. I looked and it read, ‘Made in Japan.'” Everyone laughs. Y.A. is on a roll. He is trying hard — too hard — to convince everyone that as a single man he rarely exploited his fame for any backseat pleasures. “I would sometimes get a kiss,” he says. Just then, Anna brings a plate filled with Y.A.’s medicine, tethering him to his current reality. “Anna!” Y.A. says. “I’m telling a bunch of lies over here and getting away with it — until you brought these pills.”

For a moment, at least, nobody is searching for a glimpse of what Y.A. Tittle used to be. They’re enjoying what he is. A few minutes later, Dianne watches with pride as he heads toward the door, waving off any help. “I can walk anywhere,” he says. “I can run anywhere.

“I can still play football.”

Tittle throws one of his record seven TDs against the Redskins in 1962. Kidwiler Collection/Diamond Images/Getty Images

THE NEXT DAY, Dianne, Anna and Y.A. board their 6 a.m. flight back to San Francisco. A tornado is destroying the region. Dianne is bracing for another rough trip. Y.A.’s cough seems to be worse, and Dianne knows that very soon her dad will forget about the party. Yesterday afternoon, discussion turned to the plans for the night. Y.A. said, “We’re having people over for the party, right?” A bit of the color drained from Dianne’s face when she heard it.

But the plane takes off smoothly, leaving the storm behind. In the air, Y.A. breathes easily. No oxygen is needed. When they land back in California, where time and memory stand still, he says to Dianne, “That was one of my best trips home.”